Monday, 17

Tuesday, May 11th. It is worth mentioning, for future reference, that the creative power which bubbles so pleasantly in beginning a new book quiets down after a time, and one goes on more steadily. Doubts creep in. Then one becomes resigned. Determination not to give in, and the sense of an impending shape keep one at it more than anything. I'm a little anxious. How am I to bring off this conception? Directly one gets to work one is like a person walking, who has seen the country stretching out before.

Woolf, Virginia. A WRITER'S DIARY: Enriched edition. Modernist musings on stream-of-consciousness, identity, and the craft of writing, drawn from intimate diary entries (pp. 39-40). (Function). Kindle Edition.

the same happens to me with my pictures.

by the way, i unhang my last one and stored it and started a new one today.

Sunday, 16

sometimes i try to remember how it was like six years ago when we moved into this house. what was going through my mind?

when i look back at my diary from 2019, i'm struck by how i arranged it. the layout speaks louder than the words. the images are huge, stretching across the page as if they needed to prove something to me—or hold me in place. the lines run far too long, nearly unreadable.

the person i was then didn't quite trust language. the photographs took up the space the words couldn't. i was living in a new place, unsettled, overwhelmed, and a bit frightened. the oversized pictures were my way of saying This is real. This is where i am now.

i don't think i want to change any of it. the layout belongs to that time. it shows the architecture of a mind still searching for its ground, stretching, experimenting, longing for connection. my sense of belonging was more uncertain than now.

Saturday, 15

today i read Emanuele Coccia's reflection on Alfred Sohn-Rethel's time in Naples, where he observed that the essence of technology lies in the functioning of what is broken. in Naples of the 1920s, machines did not work because they were intact; they worked because people constantly reinvented them. brokenness was not an exception but the very condition under which life unfolded.

this thought immediately connected to my experience here in Gambia.

things often function not because they follow a modern logic of efficiency, but because someone improvises a path for them to continue. the fan that starts again after a creative twist of wire, the water pump coaxed back to life. a car moves because the driver has invented a sequence of gestures that would bewilder a mechanic from anywhere else. the fragile infrastructures that persist through daily acts of ingenuity.

Coccia calls Capri a historical-metaphysical oasis where modernity’s ambition to dominate objects collapses. gambia sometimes feels like that, too. a place where modernity’s smooth surfaces crack open and something more human—messy, improvisational, alive—emerges instead. it creates a different relationship with the world of objects. modernity wants autonomy, smoothness, control. but here objects demand attention, collaboration, even care. they refuse to disappear behind automation; they pull us back into the material world and make us responsible for it. life does not wait for perfection. hence, the broken can become the very medium through which a different kind of intelligence appears.

perhaps this is why living here feels so alive. the world is constantly in the process of being remade, not through grand plans but through countless small gestures of repair. a continuous, collective reinvention of reality.

in this sense, brokenness is not only a flaw; it is a mode of being. a reminder that the world is always unfinished—and that its continuation depends on us.

Friday, 14

age reveals itself in subtle ways, not only in the body but in the mind's shifting ability to remain flexible. when movement is neglected, stiffness settles in, and that physical contraction seems to echo inward—thoughts lose their ease, possibilities narrow, and habits become so entrenched that they can no longer be questioned.

watching my mother, who will soon be ninety, i sense a similar shaping. perhaps she has always been a little careful; perhaps time has simply drawn a finer line around the way she moves in her world. born in 1936, she was a child of wartime scarcity and became an adult in the atmosphere of post-war reconstruction. stability, rebuilding, and the pursuit of prosperity shaped the tone of her young adulthood. major changes, as i remember it, meant for her rearranging the furniture. we children grew up in a different atmosphere. we took different kind of risks believing that change was not something to fear but a force that could enhance our lives.

within me, both her cautious steadiness and the adventurous openness that has characterised my life coesxist. desire though, when it roots deeply, can harden into a kind of desperation that fixes me in place. longing becomes a grip—it directs, yet it can also blind, narrowing the horizon to a single path.

however, there are those luminous moments when that grip loosens, consciousness expands and the mind suddenly widens and breathes again—a shift from insisting to gently wondering and being curious. a plan transforms into an unexpected doorway.

habits remain few, aside from my morning coffee. but even that feels secondary to a deeper wish: to greet the unexpected without resistance, not as disruption but as a gentle guide, and to choose rituals that hold me lightly rather than chains that hold me fast.

Thursday, 13

i continue to read Virginia Woolf's diary, but i find it difficult to grow fond of her voice. her way of judging people and situations unsettles me. she views many things very negatively, almost with a cold, calculating gaze. her worldview is overshadowed by a constant, underlying dissatisfaction. i miss her understanding of people who don't meet her expectations. the way she writes about servants strikes me as arrogant. her ambitions towards others and herself seem so high that they leave little room for gentleness or ease. this restlessness emanating from her diary makes it hard for me to read it continuously. i can only take it in small doses. her brilliance is undeniable, but her criticism feels heavy, almost like a strong, bitter medicine.

Wednesday, 12

1919 Virginia Woolf A Writer's Diary

Wednesday, March 19th.

Life piles up so fast that I have no time to write out the equally fast rising mound of reflections, which I always mark down as they rise to be inserted here. (page 22)

Monday, January 20th.

I note however that this diary writing does not count as writing, since I have just re-read my year's diary and am much struck by the rapid haphazard gallop at which it swings along, sometimes indeed jerking almost intolerably over the cobbles. Still if it were not written rather faster than the fastest typewriting, if I stopped and took thought, it would never be written at all; and the advantage of the method is that it sweeps up accidentally several stray matters which I should exclude if I hesitated but which are the diamonds of the dustheap. (page 20)

Woolf, Virginia. A WRITER'S DIARY: Enriched edition. Modernist musings on stream-of-consciousness, identity, and the craft of writing, drawn from intimate diary entries. (Function). Kindle Edition.

Tuesday, 11

today a warm, sweet-smelling wind is blowing. in switzerland, they call it the Föhn, which literally means hairdryer.

yesterday i made a poor decision.

the past few days had been dim, the sun hiding behind clouds, and even a heavy rain—rare for November—had fallen. i hesitated over the laundry, unsure whether to wash or wait. the solar batteries weren't yet full, so i delayed. however, something in me whispered that not washing would be a kind of omission—especially since i planned to stay in town until sunday and would leave behind a big pile of dirty clothes. when the batteries were finally charged, i ran a short 30-minute cycle.

by ten o'clock last night, the power was gone. it did not return. such abrupt blackouts are typical here—gifts from the electricity company NAWEC. one waits in faith, expecting the light to come back. but with empty solar batteries, that obviously doesn't happen. we had to accept it.

now, at 7:30 in the morning, the system still won't start. it reminds me of earlier years, when during the rainy season the solar power would often fail. my main worry is the refrigerator—and the frozen fish it guards.

today i finished Les Mécaniques des Souvenirs. in the end, it turns out that Moïse shot his father, and the monologue in the last chapter is addressed to his father's corpse. i'm sorry to spoil the ending, but i don't think it's crucial, at least not for me; the essence of the book lies in the journey of reading through it. personally, i find the ending quite drastic—although, since he himself likes and writes crime novels, it somehow fits into Njami's narrative tradition.

Monday, 10

my abstract experiment is finally finished—or at least it feels that way. i'll let it hang for a few days, to see if it still speaks the same language when i am back from Kololi or asks for a small change. for now i just want to share it as it is, in its current state of becoming.

Sunday, 9

sunday is best. i sleep in and feel the most free.

this morning, before i got up, i had vivid dreams about my sister. i think reading the novel contributed to this — especially the intense relationship between Moïse and Sarah.

i'm writing with a translation app. of course, the app always knows best and strictly follows grammar and spelling rules. this makes playing with language tricky. if i want to keep my original phrasing, i have to correct it afterwards — and often i forget, too caught up in what i'm trying to say.

a simple example from today: i write Sunday is best, and the app insists on Sunday is the best day.

---------------------------

yesterday's entry was about Moïse and the image of reflection—seeing oneself through the fragments of another's story. today, i've continued reading the monologue addressed to his father, a passage soon after the one i quoted yesterday.

Je pourrais te dire mes craintes, mes angoisses. Cette peur de n'être pas à ta hauteur. Cette angoisse à devoir endosser un costume taillé pour d'autres. Comment font donc les enfants devenus grands ? Deviennent-ils des adultes ou bien continuent-ils, toute leur vie, d'être des fils et des filles de… ? Des êtres sans caractère propre, parce que fruits d'une autre chair ? Modelés par d'autres instincts qu'ils croient devenus les leurs ? « Tu lui ressembles », m'avait dit Ariane en découvrant une photographie sur laquelle tu posais, quelques années avant ma naissance. Est-ce donc cette ressemblance-là, cette évidence que j'ai voulu abolir ?

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 326, Kindle Edition

and now i'm not just talking about the parents who shaped us and whom we resemble. the impulse to measure my worth based on what others might see or expect is a tension that arises from affection and judgment, which are intertwined. it also means a form of communication. at times it can feed inspiration. what is my art work if not seen through the eyes of others?

in other words, the balance between criticism and recognition is a driving force to continue and possibly impress others. if it's only about control and the attempt to corner someone's work or life, then it leads to fear.

Saturday, 8

Il n'est pas un livre que j'aie écrit que tu n'aies pas lu. J'en ai la confirmation aujourd'hui mais je l'ai toujours su. Je n'avais pas besoin des preuves enfermées dans le double fond de ton bureau. Que nous n'ayons jamais pu en discuter ensemble est un manque qui ne sera jamais comblé. Et puis maman est morte.

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 326, Kindle Edition

it resonates with my own relationship to my parents, especially with my mother. she wanted to be fully informed about my work—not only out of curiosity, but almost as if she needed to guard the gate between me and the world. her comments, even when admiring, often carried judgment. for a long time i wanted nothing more than to please my parents. i see now how much of my artistic path has been an effort to escape that gaze, to define myself beyond their expectations.

it took me a long time to achieve that distance, to stop measuring myself through her eyes. but i did. i no longer imagine her reactions when i finish something—that reflex has vanished. what remains now is a quiet neutrality, not bitterness, not even sadness, but a kind of peace that allows her to exist outside my creative process, and me, finally, outside her judgment.

when i read about Moïse, i felt like i saw myself reflected in different facets.

Friday, 7

the house where i live is truly beautiful. especially in the morning—the silence, the birdsong, the cool sun, the scent of the sea. the large garden gives space to feel the air and the light. it is as i dreamed of, and i am thankful that i could realise it.

however, somehow it's sad that in all these years no one from my family has ever visited me, and none of my friends since those early days. when i had just moved in, a befriended couple from switzerland came. i was still still finding my ground and finishing the construction. later, when everything had settled, there was no one from abroad to share it with. my parents were too old and could no longer travel. but my siblings and their families? well, that's just how it is; i can live with it and still be happy.

sharing what matters to me with the people i love used to be essential back in the days—it shaped the way i saw and understood things. it was through them that my joys felt full, my thoughts gained depth, and even my struggles found meaning. the presence of others, their attention, their understanding, gave life a kind of reflection i could not find alone. it was a way of feeling truly seen, and of seeing myself clearly in the world.

that time has passed, and i am now able to create my life alone. what remains is something quieter, more like being satisfied with oneself—the simple joy of being here, in this place that feels entirely my own. what do i want more. for sure, i believe that is enough.

Thursday, 6

why do women say that their partners are very helpful—that they cook, drive them around, participate in housework, support them professionally or even carry their bags? they say it with gratitude, almost as if these gestures were little gifts. however, i've rarely heard a man emphasise that his partner helps him with his duties and daily routines.

do these men simply take their partners' support for granted—or if they don't even perceive it as help? probabaly not, because it's embedded in emotional support, in organizing daily life—the kind of attention that sustains relationships without demanding applause. they think the women do it very willingly and wouldn't need any words of appreciation.

on the other hand, my late aunt (who had never lived with a man) used to say that a very important thing about a man is that he helps. my unspoken thoughts about her words were definitely of a different nature—spiritual. for me, a relationship was based on platonic understanding and erotic attraction. to my ears, her words sounded almost calculating and reduced the man to someone whose worth could be measured by the tasks he fulfilled.

in this context the word help is gendered. why should it be worth mentioning that a man participates in the same responsibilities that constitute a shared life?

it's time to leave the notion of help behind. the word already implies that the work belongs to someone else. what if we spoke instead of sharing—of living together as two people who care for the same space, the same meals, the same dreams?

perhaps then we wouldn't have to thank men for their help anymore, or wait for women's caregiving to be noticed. we would simply acknowledge that the work of everyday life belongs to both of us.

Wednesday, 5

i need a new book so i can maintain my morning reading habit. i only have two chapters left of the book i'm currently reading. it's going to be difficult to find something that captivates me just as much.

i've already started many books in my kindle library. maybe one of these: The Diary of Anaïs Nin — almost read, 87%; African Art as Philosophy by Souleymane Bachir Diagne, 15%; Who is afraid of gender by Judith Butler, 5%; A Writer's Diary by Virginia Woolf, 2%; Black Bazar by Alain Mabanckou, 7%; Poetics of Relation by Édouard Glissant, 7%; Dream Count by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 43%; In the Wake by Christina Sharpe, 27%. these are the books i've bought, fully downloaded, and opened in the last several months.

i think i would never want to write a book that resembles an autobiography. too many shadows, too many experiences that i don't wish to describe—stories that don't need to be told, unless maybe here, sometimes, in this shorter form of diary entry.

this morning i read a sentence that reminded me of yesterday's entry, where i regretted not having taken better care of Maria.

Les remords ne servent à rien. C'est un truc practique pour s'absoudre de n'avoir pas agi.

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 308, Kindle Edition

Tuesday, 4

my neighbour, a german woman by birth, passed away last night. i'm so sorry to hear that. we hadn't been in touch for a long time. i kept asking about her, but nobody could give me any information.

when i passed by her property on my walks, her dogs would bark and sometimes come out to chase mine. i always looked to see if i might catch a glimpse of her.

she never contacted me.

in the beginning, i sometimes saw her on the street—we even visited each other and once celebrated new year's eve together. later, she lived a very secluded life. from time to time i saw her daughter or her son and we exchanged a short greeting. my partner occasionally sees her son at the mosque on fridays, but they haven't talked about her, as he told me when i asked.

and again, i have this feeling that i could have done something to save her. my own inability to accept death as something natural—something that happens to everyone—and my inability to let go of this feeling of responsibility weigh on me.

she's being buried today. as is customary, the funeral is taking place on the same day. Rest in Peace, Maria.

Monday, 3

suddenly my mood shifts. i'm positive again. in the mornings, after waking up, my thoughts are sluggish, and i wonder how i'll get through the day. but eventually, i reach a point where i no longer feel any resistance. luckily, this happens very quickly now, in less than half an hour. it used to take hours. sometimes i even complained about life's hardships at breakfast. what a burden that was for the person opposite me.

what fascinated me about Shakespeare—and equally about Bruce Chatwin—is the tension between truth and fiction in their narratives. just like in Njami's book.

a diary, after all, seems to promise truth—a record of reality, preserved day by day. yet every word transforms experience. writing turns life into language, and language itself becomes a kind of parallel reality. language is a medium.

the use of language is certainly reality, but so is the reader's imagination, which cannot be foreseen and at first remains private, intimate, until it resonates with others.

through writing, i shape what i think and what i have lived, framing it in a form i believe is worth sharing. my goal is to remain authentic, while the use of truth and fiction remains fluid.

Sunday, 2

simply want to write down the words that come to mind.

i've burned myself. i thought the coffee had already cooled down. it's early morning and i'm sitting on the balcony. i'm thinking about Napoli. that month when we filmed. i loved the warm mediterranean climate.

this will be an associative month, i think. i'll just let my thoughts flow and worry less about the proposals given by the ai. i want to respect my own words more. even when there are more flaws.

the rhythm of La Méchanique des Souvenirs is influencing me. after reading it, my thoughts appear in a similar beat.

i'm thinking about the time i translated Nicholas Shakespeare's The Vision of Elena Silves into german. chapter by chapter, if i remember correctly. it was in the 1990s. after finishing a chapter, i printed it out and stapled it in our folders.

the pavilion has been empty for some time now. partially furnished. i don't care. i don't really seek out human contact. the walls for the chicken coop are up.

my skin is constantly wet. i get rash from that.

i wonder if looking at their phone means the person wants to appear busy—a kind of fake news.

Saturday, November 1

names change, life moves on

sometimes i wonder

if people are searching for me

that's how i do

i was

born Maren Schmidt

later became Maren Schmidt-Löffler

then i was Maren Schaffner

today i am Maren Sanneh

or Mimi Sanneh.

if you know me

under one of these names

and happen to find this page

WELCOME

Friday, 31

i'll say it right away—or rather, since it's already the last day of the month: this is turning into a double issue. i haven't finished the book yet, and besides, i have no idea what i'm going to do for the Work of the Month, which will stay the same in november.

yes, i'm enjoying it deeply and feel genuinely excited about what lies ahead. there are ten chapters to go. when i started the book, i read it slowly, in French, savouring the language and pausing often to look up words. later, when i was eager to grasp what was happening, i switched to reading just the translation—for a while even whole pages at once. i only checked the french original (which, thankfully, is not in Bassa), when i wasn't sure about something.

now i've returned to my first way of reading: beginning with the original text, then looking up the meaning of individual words, many of which sound familiar through their Latin roots in english. occasionally, i look up entire sentences when their meaning slips away.

additionally, my curiosity leads me further. i find myself looking up places on maps or researching terms and figures i don't know much about—like Pontius Pilate, for instance. reading has become a kind of wandering, a way of moving between languages, histories, and landscapes.

it takes longer this way, but i prefer it—absolutely. it feels like entering the text more fully, as if i'm walking rather than rushing through it. it's not about reaching the end. it's about following a path that carries me somewhere subtle and unexpected.

Thursday, 30

i didn't even last a week. after just two days, i was done, and now i'm back. the apartment was unbearably hot; there's simply no way to cool it down properly. during the night, the bedroom stayed around 30°C. impossible to sleep comfortably in that kind of heat.

further, tasks are waiting for me. my picture is calling, though i forgot the red coloured pencils i specifically bought at Aunty Bee in the Tropic center for the final step. i'm almost done connecting the spaces in between (with reduced colours). and with the weekend approaching, i hope we'll go back to town again for a short trip, insha allah.

i tell you, even here in tintinto, it's very warm. not even 8 a.m., and i'm already starting to sweat. in the so-called office where i am at the moment—the laptop hasn't made it into the studio yet as we arrived yesterday afternoon—it's already 30°C. actually, not much different from town, but the breeze here in the open surroundings feels somehow stronger.

then... the internet connection is a pain in the butt. although i chose a more expensive version for this month i restart the router continuously. i must talk to them.

Wednesday, 29

PARADISE AND OBSERVATORY

what i have built has been called paradise. the word flatters me, yet unsettles me.

even though i know it's meant as a compliment.

what better thing could one hope for than to have built one's own paradise?

to me it implies fulfillment and harmony—a place where nothing more is needed.

and yet i hesitate before it. i've never imagined such a place for myself.

if paradise existed, it would be there for all.

perhaps i call it an observatory.

it lacks the glow of paradise, but represents a withdrawal from the compulsion to achieve towards a quieter form of participation in the world.

light shifts, seasons pass, and meaning emerges without force. patience replaces purpose, perception replaces ambition.

"Observatories make more sense than enterprises nowadays," someone wrote to me.

and i agree. enterprises belong to a world of constant acceleration and measurable results. observatories accept imperfection—the tension of incompletion—as the condition of understanding.

even the briefest acknowledgment can shine like a quiet light within this observatory.

to be seen, however lightly, is itself a form of paradise—subtle and enduring.

in that light, the world becomes inhabitable, generous, and ours.

Tuesday, 28

i come across the word nonchalance (page 264)—a word i remember from my mother, from back in the day, when she used to say it with a tone i somehow understood instinctively without needing to ask. i haven't heard her say it in a long time. . . but now, seeing it i can't quite translate it.

here's what the AI says: Nonchalance means a calm, relaxed, and unconcerned attitude — especially in situations where others might expect excitement, worry, or enthusiasm. Someone who shows nonchalance appears cool, indifferent, or unbothered, even when something serious or emotional is happening.

nonchalance seems to contain something subtle—a philosophy of being. it is the art of not being consumed by what happens, of standing lightly within the flow of life. my mom must have known this. in her voice, the word did not sound careless, but free—a gentle refusal to be disturbed by the noise of the world.

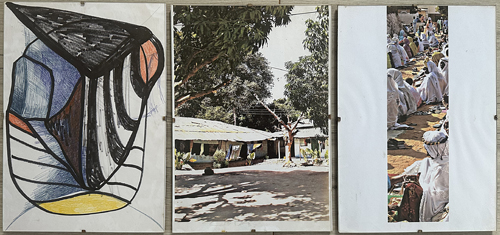

Triptych - avendre 85 / 174 / 131

another triptych was created today, and three of my Avendre works went into other hands. i hope they will be treated with care—especially the left drawing, which is more than 20 years old and carries an immediacy that i rarely reach again. something i don't give away so easily. the other two are inkjet prints, more reproducible. still, when they were chosen, i coudn't object.

Friday, 24

BLUE NOTE

the following quote comes from a passage in chapter 35, where Moïse and his brother Isaach, the musician, walk together by the lake in Lausanne and Moïse asks Isaach whether he had reached the blue note.

Isaach explains that the blue note is the sound that trembles between harmony and dissonance—slightly off. it carries the weight of feeling, the human imperfection that transforms technique into emotion. for Moïse, it becomes more than a musical concept. it mirrors the very texture of memory and life itself, those moments of deviation, loss and vulnerability that give existence depth.

the quote evokes the feverish idealism of youth—that conviction that creation must justify itself through suffering, rebellion, or madness. to be true was to be misunderstood; to conform was to betray one's essence. yet time teaches a quieter lesson: that resistance, when it becomes a posture, can imprison as much as obedience. what remains, then, is the subtler task of discerning where freedom truly resides—not in defiance or compliance, but somewhere in the fragile space between the two.

Adolescents, nous ne pouvions pas nous imaginer autrement qu'auréolés de gloire,

reconnus par nos frères humains pour un talent supernatural. C'était cela ou mourir. Dans la misère, si cela était possible. Seule la misère pouvait valider la vérité de notre génie.

Ou la folie. Comme Artaud et Van Gogh, comme Mozart. La note bleue. La plus belle des notes. Le Graal de tout musicien de jazz et par extension, sans doute, l'aboutissement

pour quiconque se prétend un créateur.

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 186, Kindle Edition

but life soon corrected that illusion. we discovered that rebellion alone is not the freedom we were searching for—and that the price of constant defiance can be loneliness. what began as resistance turned into exhaustion. resistance was met not with admiration but with distance. i realised that freedom without connection can become another kind of confinement. so, gradually, i adapted.

now, i no longer seek to be exceptional or obedient. i simply want to understand why the question "is this appreciated?" still echoes within me. it's not the world's judgment i fear, but the remnants of my own conditioning—the child who learned that love was contingent on compliance.

the mature task is neither to reclaim that youthful arrogance nor to settle entirely into conformity. it's to find a new kind of freedom: one that doesn't depend on rebellion or approval, but on lucidity. to see the fears for what they are—traces of old conditions—and to act from a steadier, self-authored, self-determined space.

(The "blue note" — la note bleue — refers to a slightly lowered tone in blues and jazz that gives the music its unique depth and emotion. It also symbolizes the elusive moment in art when imperfection becomes beauty—the artist's unreachable ideal, the point where truth and feeling meet.)

Thursday, 23

since the rains began, the paths are covered in mud. everyone comes to the gym in thongs, carrying their sneakers to change into once inside. i do the same, though my car is only a few meters away. only one person walks through the dirt in their training shoes and then keeps them on to exercise.

i find it disturbing—not because of the mud itself, but because of the attitude behind it. it's not mere carelessness, but almost a performance: a way of saying we have nothing to protect, nothing worth preserving.

to look after things, to keep them clean, is to affirm that they matter, that one's surroundings matter. the deliberate refusal to do so feels like a quiet denial of that idea, a claim of exemption from consequence, as if value itself were no longer relevant.

And yet… it is none of my business.

Wednesday, 22

of course, i make mistakes in this journal. sometimes my writing moves like a dream—half-awake, half-lost, as if my thoughts were walking ahead of me. to return later often means to find words misplaced, thoughts unfinished, sentences that seem to belong to another mood entirely, wrong dates, inaccurate graphics.

for sure i will correct them, gently—as one might smooth a wrinkled sheet or brush sand from a path. it's a small ritual, tender.

i know this weakens the raw truth and authentic character of this document, but i also know i can't leave untouched what disturbs me.

so i take the liberty: to rewrite what was once unconscious, to mend the small cracks of language, to make the silence between the lines a little clearer.

Tuesday, 21

J'ai ecrit "Chère sœur". Puis, pensant que cela avait une connation trop familière, trop intime, trahissant une volonté de créer une complicité artificielle, je me suie rabbatu sur un "Chère Sarah", plus neutre.

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 186, Kindle Edition

this hesitation between sœur and Sarah reveals how delicate the boundaries of intimacy can be—how a single word can shift the distance between two people. it reminded me of my own sister. whenever i visited her, or when we spoke on the phone, i would hear her say to her boyfriend, "My sister is here," or "I'm talking to my sister right now." each time, i felt slightly alienated. why didn't she say my name? it sounded as if he didn't know who i was by my name. yet it wasn't about him—it was about her way of situating herself.

saying my sister was, in a sense, drawing me closer to her while at the same time pulling me away, as though i existed only in relation to her. the possessive my made the connection personal, but also proprietary. sister defined the kinship. it affirmed closeness while creating distance.

this tendency wasn't unique to her. it ran quietly through our family. my father often referred to his own relatives in the same way—"my brother," "my mother"—rather than calling them by their names, as we did. and it always made my mother slightly tense, the language of possession can subtly exclude, even within the most intimate bonds.

in a way, the family map explained it. my father had fully integrated into my mother's family. his parents lived somewhere in england, his sister in thailand, and only his brother remained nearby, sometimes dropping by unexpectedly and paying us a surprise visit. those unannounced visits were a reminder that language and belonging aren't fixed—they shift depending on who is near, who is far, and how we define our closeness.

if i remember correctly, my mother was not enthusiastic about these visits.

perhaps that's what Moïse (the narrator in Njami's novel) expresses in his hesitation: the uncertainty of where we stand with one another, and the quiet realization that every word—even a greeting—carries the weight of our emotional geography.

Monday, 20

i discovered the existence of Simon Njami's book La Mécanique des souvenirs two weeks ago. since then, the book has accompanied me like a quiet undercurrent. my intention was to write about it only after finishing it, but halfway through, i can't hold back. it moves me deeply. the text resonates with my own experience of living in Africa—that shifting tension between proximity and distance, between belonging and estrangement.

i often experience what he calls le décalage—that misalignment between where one stands and where one belongs.

Déjà le décalage que j'avais ressenti à mon arrivée s'estompait. Le pays essayait de me dire quelque chose. Et je crois que je commençais à l'entendre. Si la matière de l'écriture ne réside sans doute pas dans ce que l'on note, mais dans tout ce qu'on oublie, je suis en bonne voie. Je réinvente mes souvenirs, les adapte à mes désirs.

Simon Njami, La Mécanique des souvenirs, p. 178, Kindle Edition

Njami's idea that writing draws its substance from what is forgotten, not only from what we record, opens a new way of thinking about memory. it suggests that memory is not a fixed archive but a living material—something we shape, bend, and transform.

reading La Mécanique des souvenirs here, amid my own surroundings, i realise how memory is conditioned by place. the Africa i inhabit is not the same as Njami's, yet through his voice i sense a shared movement: the negotiation between inner landscapes and external realities.

Njami is not only telling his own story but also helping me to read mine. yet, as he writes, "the gap I had felt when I arrived was fading. The country was trying to tell me something. And I think I was beginning to hear it." he names something subtle: the slow moment when a foreign place stops being just "elsewhere" and starts to turn towards you, as if it recognizes you all of a sudden. it's not about belonging in the conventional sense, but about entering into a conversation with the landscape, the people, and one's own memories.

Njami's book is less an autobiography than a meditation on identity as flux, on how identity is constantly being rewritten. his "mechanics" are not mechanical at all; they are human and fragile, built from loss, imagination, and desire. to read him is to be reminded that our stories are never complete. each day rewrites them, balancing what we remember against what we let go.

Sunday, 19

in the morning, i'm not allowed to ask anything. just serve.

there must always be a mission behind everything we do.

what is the mission?—the question returns each time i suggest an action.

the idea of simply enjoying something, taking a moment for ourselves, doesn't fit into the framework. except at night, when we go out for party. but a simple walk on the beach—what's the point?

pleasure without a deeper purpose seems suspicious.

it took a lot of persuasion to make this weekend possible. it was about a change of scenery, to be more fit to start the following week again. yet even that—rest, recovery—needs to be defended, as if it were an indulgence rather than a necessity.

anyway, we finally made it, and for me, it was a bliss. now that i'm back, i feel very refreshed. next time i'll go alone again for a week, that seems more appropriate.

Saturday, 18

we're in Kololi, treating ourselves to a break and enjoying the Dolce Far Niente.

the heat makes our bodies feel heavy.

across the courtyard the children play on the veranda. they are loud again, their voices echoing. when i was here longer, the screaming gave me a headache. now i don't care.

the smell of freshly baked cake wafts over—soothening.

amazing how a scent can enliven the senses.

i think of everyone who bakes. a quiet kind of generosity.

nothing for me anymore. i wouldn't like the smell if i baked myself. i used to, as a teenager. later, sometimes, too, but that was years ago.

i'm glad others still do it.

Thursday, 16

i wonder if the nature of an experiment must justify its steps, or the act itself as a whole.

in my current work, i deliberately chose the colours blindly—without reference to colour theory or preconceived harmony. the intention was to let the process decide, to discover what would happen if i surrendered control.

at times i'm afraid of the outcome—as if the painting might reveal something i didn't mean to show. or that something might occur, like a crooked line, a collision of tones, that i wouldn't usually allow to remain—an imballance i would normally correct.

perhaps this discomfort is part of the truth. it confronts my own aesthetic expectations and questions the boundaries i have built through habit and preference..

the justification of the experiment does not lie in order or reason, but in its authencity—in allowing the painting to become what it wants to be.

when the work feels stronger than me, it begins to speak its own language. it takes on a life of its own. that experience is not entirely new. in earlier paintings, i also sensed unpredictability. the transformation from photo to drawing has always carried uncertainty—the movement of the pen could never be fully anticipated. yet, in this current work, uncertainty itself has become the subject. the focus is no longer on translation, but on the random encounter between colour and form.

Tuesday, 14

IN THE GYM

words fly like birds

twisting through the music

i move alone

some work in groups

their laughter weaves

a net i cannot enter

i walk

as if in a bubble

sometimes i drop

a phrase like an anchor

a moment of ease

newcomers stare

their gaze too long

difference is a stranger

still, i train.

that's how i get through

that's why i come

from somewhere behind

a voice claimed:

he is collecting paper

it stuck to me,

light as a feather

sharp as a beak

i

don't know who he is

nor what paper means

but the words won't leave me

unless i bring them

to let them go

over the years, i've met a few of white european women living in gambia. about half have carved out lives of success. most of these have been around for twenty years or more, building thriving businesses and establishing themselves firmly. the other half, newer arrivals, live differently. they drift like beachcombers, fallen for or hanging out with beachboys, surviving more than living, drawn to freedom rather than structure—dropouts, in a sense, from the world they left behind. sometimes trying to gain back what they had been taken from.

i came here with a plan, a vision rooted in art and culture, after much preparation and reflection. and yet, sometimes i wonder if, in the daily unfolding of life here, i am moving closer to the second group—not by conscious choice, but because circumstances make the familiar frameworks of the Western world feel distant and irrelevant.

rural gambia reshapes intentions in subtle ways: the rhythm of life, the available structures, the social expectations, even the pace of days—they are all different from what i knew before. it's not merely a matter of material success; it's a question of identity. how do i define myself between these two models: the long-established, business-oriented women, and the free-floating wanderers? i am neither and both. i am creating something meaningful, but within a context where familiar rules of recognition and progress do not always apply. perhaps it's less about moving toward or away from western norms, and more about allowing a third identity to emerge—one shaped by this in-between space i inhabit. structure and purpose remain, yet the form they take has adapted to the surroundings.

Sunday, 12

i came across the word immaculate and realised how unfamiliar it feels to me. i never use it. perfect would be rather my word of choice—though, i rarely encounter anything that could be called immaculate.

we spent the afternoon at the beach. it was beautiful: the sand, the sea, the calmness of it all. last night, rain poured down again, heavy and steady. the puddles in the streets are overflowing once more. they say the climate is changing, that the rainy season now stretches into october. the october used to be dry before.

Saturday, 11

i'm undecided about how to proceed.

the third step isn't complete, yet my thoughts already move beyond it.

perhaps this is part of the process itself—one gesture still forming while the next begins to imagine its own arrival.

creation never happens in sequence; it spills forward, overlaps, anticipates, as if the work itself were thinking ahead, imagining its own continuation.

i'll probably connect the inner pieces next.

i know i'm speaking in riddles, but that's how it is when things are still in becoming.

once the picture is finished, it will show what i try to explain.

for now, only the words can stand in its place.

i had considered reducing the spaces between the pieces to the colours of fire.

the inkjet prints of the fire have remained part of the whole, faintly echoing their source, as traces of something that once burned.

yet when i made the draft, the result felt too warm, too natural—too obedient to what fire already means.

i'm searching for something that radiates, that projects energy outward rather than absorbing it.

probably a pause will be needed after this third phase.

not as delay, but to let hesitation be part of the experiment—a moment of quiet in which the work itself can speak,

and i can listen to what wants to happen next.

Friday, 10

here and then i feel the wish to speak about my experiment.

i think that belongs to the nature of an experiment. sharing is part of it, like exploring what is happening and encoutering different perspectives— before it is fully understood. only through dialogue, even with oneself (like i do) does the process reveal how it might continue. yet speaking about something still in motion risks solidifying it too early. the unfinished gesture should remain unbound when exposed to someone's gaze.

language leans towards definition, toward coherence, while an experiment thrives in uncertainty, in the vastness of what cannot yet be clarified.

there is that fragile instant between sensing and naming, when things are still forming, undecided.

once language enters, the fluid begins to settle; outlines appear, meaning starts to lean toward conclusion. still, the wish remains—to see whether uncertainty can survive in words, whether vagueness can persist once spoken.

the talking is not outside the experiment at all, but part of it. another gesture within the same field of exploration.

Thursday, 9

lately, i've been experimenting with abstract painting by choosing colours blindly, without intention, without meaning, yet even in this attempt, a sense of inevitability emerges.

the phrase Das ist so vorgesehen came to mind. each colour began to feel strangely predetermined, as if it had been waiting for me, already arranged somewhere in advance.

Vorgesehen literally means "foreseen," but in everyday german it sounds final, administrative. it doesn't suggest possibility; it closes it. when something ist so vorgesehen, it is not to be questioned. one's only task is to follow. there is no space left for improvisation, it has been seen already.

in the studio, i recognize that tone of quiet insistence. even when i try to act freely, meaning seeps in. even when i attempt to let the work decide, something in me insists that it was always meant to happen this way. creation, i realise, is never free from what is already seen—only a negotiation with it.

perhaps that is what vorgesehen truly exposes: between freedom and predestination lies a space of gestures that feel both inevitable and accidental, as if the future had glanced back at us before we began.

Wednesday, 8

the following phenomenon somehow shaped my life:

i feel guilty when i do what i like.

it's as if joy needs to be justified. a part of me believes that pleasure must be earned. whenever i follow what gives me pleasure or meaning, a voice inside whispers:

do something harder, more useful, and less selfish.

as soon as i enjoy myself, i start feeling uneasy, asking whether what i am doing is wrong. but when i push myself to do what i don't enjoy, i feel like i'm being good, useful, and disciplined.

i do understand where that comes from. i learned that being loved or accepted meant being responsible, helpful or good. pleasure was a luxury, not a right. enjoyment came second. culturally, i absorbed the idea that self-denial is virtuous, and that ease means laziness. comfort or joy seemed suspicious. (the time i moved to Gambia i declared i was leaving my comfort zone)

i've carried a deep empathy for others' suffering, feeling that my own happiness somehow betrays them—which is even a lie. my allegedly suffering won't help people in need at all.

i learned to measure my worth through effort and sacrifice.

i carry an invisible loyalty to others who have struggled more. i often think,

who am i to rest or enjoy myself whilst others can't?

these thoughts have kept me from allowing myself a peaceful mind, as well as from things that bring me alive—art, beauty, curiosity, rest.

i want to unlearn the idea that suffering makes me good and pleasures make me guilty.

i want to give myself permission to do what i love—not as a reward, but as nourishment, as a natural part of being alive.

from now on, when the guilt shows up, i'll name it without obeying it. i'll remind myself that the rule "you must earn joy" is no longer true. i'll let pleasures coexist with responsibilities—doing my artwork even when chores wait, resting even when my mind protests. smiling without apology. hopefully with time, i am able to make space for both responsibility and joy, without feeling like one cancels the other.

Tuesday, 7

Oliver Stone's documentary on the Palestine/Israel conflict (2003)

People Non Grata

Monday, 6

yesterday, on the road back to Tujereng, someone waved from a passing car. it was cousin A. i asked whether i should stop, but the familiar answer came: you are driving. the decision was mine, though it seemed to carry no particular meaning.

A greeted my partner first. from there, the exchange unfolded mostly between them, in their language, which i don't understand. i followed the words like a hungry dog, alert to their rhythm but starved of meaning. their conversation drew a circle that closed just before me. i stayed where i was, listening to sounds without context, aware of how smoothly one can disappear from a scene while still standing in it. when something came to my mind i spoke it—just enough to break their flow and show i was still part of the group.

i mentioned Fireman and how we had shaken his hand the night before. A had been to a party in Sita Joyeh near the village of Kuloro, which had been great. yeah, i remembered hearing about that event.

when the talk turned to cars, i said i was not sure whether it made sense to buy a new one—that the price might equal five years of taxi rides. and the old one is still running. half in jest, i added that i might die soon anyway. A replied that wouldn't matter; i could leave the car to my partner. the sentence landed lightly, without cruelty, yet with the indifference of habit—as if my existence were already a matter of inheritance.

later, the topic shifted to visas. A stated it would be easy for me to arrange one for my partner, since he had already been to europe once. i mentioned that i had inquired at the swiss consulate at Yosh restaurant in Bakau New Town, and that the procedure was the same like before. my words made no difference. facts had little to do with the kind of conversation they wanted—affirmation and male understanding.

the talk seemed to confirm a natural order: that decisions should be mine in form, yet not in weight; that language could run its course without me. by the time we said good bye, i had grown accustomed to that small, familiar position—visible yet secondary—a presence acknowledged at the edge of things. when we finally drove off, i felt neither anger nor surprise, only the faint awareness of a pattern repeating itself.

Sunday, 5

last night we went to another party—a birthday celebration at Sunsplash in Brufut. Fireman was playing again, though this time his set was early and brief. Smokie, a young artist from Brufut whom i met when i lived there, was also performing. it was great to see him on stage again. we met many old friends, and it was pure fun catching up with everyone. the sound system was excellent—warm, groovy, and perfect for dancing. by 4:30 in the morning, i was ready to go home, happy and tired.

this morning, i met a neighbour on the stairs. she told me that she is originally from Somalia but lived in the US for a long time. we had a lovely chat and exchanged contacts. what a joy to start the day with such a friendly encounter.

Saturday, 4

Of the trio Damas, Césaire and Senghor, it has been said that the last is more of a "theoretician" than his companions—that he takes up for himself the construction of exactly those things which Césaire does not want Negritude to be: a metaphysics or a conception of the universe. For Senghor, there exists an Africanity as real as the material objects it has produced, which are, before all else, its works of art. These objects speak a language to be deciphered and they manifest an ontology that is consubstantial with the ontology of traditional religions. Senghor claims to have experienced this language, this ontology and the traditional religion of his Serer homeland and, in his poetry, he speaks of it as the "Kingdom of Childhood." This is not simply a poetic topos with no reality beyond that of a nostalgic evocation, from exile, of home as a mythic elsewhere. This kingdom is, one could say, a Platonic Idea, more real than reality itself and which reveals itself in certain encounters. For Senghor, Africanity is thus necessarily something more than a figure of dialectic—the negation of negation—a simple moment bound to disappear in the next synthesis.

Souleymane Bachir Diagne African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson, and the Idea of Negritude (pp. 26-27). (Function). Kindle Edition.

i wrote about Senghor’s understanding of Negritude last month, but i want to return to it here because Diagne captures something essential about the philosophical depth of Senghor’s vision. what strikes me is how Senghor refuses to let Negritude be reduced to a phase of reaction or resistance. Diagne highlights Senghor's effort to ground Negritude in an ontology rather than in a reactive cultural position. Africanity, in this view, is not a temporary affirmation within a historical dialectic but a metaphysical constant expressed through art and spiritual experience,. Art becomes the medium through which this being manifests, not as representation but as revelation. Senghor's thought invites us to see African art not as cultural evidence but as a mode of knowledge, one that articulates existence itself. by linking aesthetic production to ontology, Senghor situates African art as a philosophical language—one that reveals being itself rather than merely illustrating identity.

in this sense, creating—or even perceiving—art becomes a philosophical act: a way of listening to what the world already knows about itself.

Friday, 3

At times I do feel like a snail who has lost his shell. I have to learn to live without it. But when I stand still, I feel claustrophobia of the soul, and must maintain a vast switchboard with an expanded universe, the international life, Paris, Mexico, New York, the United Nations, the artist world. The African jungle seems far less dangerous than complete trust in one love, than a place where one's housework is more important than one's creativity.

Anaïs Nin, Spring 1955, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Vol. 5 (1947–1955), p 237

Thursday, 2

we’re both in a kind of denial, each of us avoiding what lies just beneath the surface.

still, we’ve returned to the gym, picking up the rhythm of training again. there’s something reassuring in the repetition—the movements, the sweat, the discipline.

it feels like we’re building strength not only in our bodies but also in the parts of ourselves we’d rather not face directly.

Wednesday, 1

Art Space Work of the Month

Pidder Auberger (1946-2012), Untitled, colour relief print, 1990, 49,5 x 37,5 cm

Pidder Auberger (1946-2012), Untitled, colour relief print, 1990, 49,5 x 37,5 cm