A phenomenon that interests me repeatedly is why people relate things to themselves, even though they are not really meant or addressed directly. And that brings me back to the topic of exclusive and inclusive.

I believe that people who have been excluded tend to do so because they have an urgency to be included. People in leading positions or those who have some form of power over others, as well as parents over their children, often exploit this need of inclusivity. They use ambiguities and sort of ambivalence to give people who are looking for recognition the feeling that they are meant and therefore included, which is actually only an illusion and ephemeral. Far from the often used term "sustainability".

On the contrary, in reality, them (those with power) abandon these actually helpless people, who feel like a star in that particular moment. I have often been in this role of relating things to myself as a means of getting connected and being on equal terms, which is the wrong way. It is a too passive action.

It usually happened somehow automatically and suddenly I found myself at the center of a topic, where I threw myself somehow inside, but where I was only the main act from my own personal point of view. An uplifting feeling, a brief moment of flying, the landing of which can be hard, when you arrive in the actual here and now. After several such unpleasant landings, I tried to switch off this relating-to-me thing and just remain in a distance, not involved. Which is actually absolutely healing. You come out of the situation unscathed and can start communication on a level based on facts.

I asked the AI:

there is a phenomenon that i am interested in: sometimes people (me included) put things on themselves even they are not meant. Why they do it?

The phenomenon you're describing can be seen as a mix of psychological, social, and cultural factors. People often take on burdens, expectations, or roles that aren't explicitly meant for them for several reasons:

1. Sense of Responsibility

Some people feel a strong internal drive to take responsibility for situations, even when it's not their duty. This could stem from personality traits (e.g., being empathetic or conscientious) or early experiences where they learned to "step in" to solve problems.

2. Desire for Control

Taking on tasks or roles, even those not assigned, gives a sense of control. When people feel uncertain, they might overcompensate by assuming responsibilities that aren't theirs to manage their environment.

3. Need for Validation

Some might unconsciously take on extra burdens to gain recognition or approval from others. Carrying these "unintended weights" can feel like a way to prove worth or competence.

4. Cultural or Social Norms

In many societies, certain roles (e.g., caregiving, leadership, problem-solving) are subtly expected from individuals based on gender, age, or position. People might internalize these expectations and act on them without questioning whether they're actually responsible.

5. Over-identification with Others

Empathy can lead to over-identification, where someone feels another person's struggles so deeply that they make it their own, even when it's unnecessary or unhelpful.

6. Fear of Conflict

Avoiding conflict or disappointing others can drive people to take on things themselves instead of saying "no" or letting others handle their responsibilities.

7. Unconscious Habits

Sometimes, this behavior is deeply ingrained and habitual. Past patterns of stepping in or assuming responsibility may continue without conscious awareness.

8. Personal Meaning and Purpose

For some, taking on challenges or burdens gives life a sense of meaning. Even if they aren't explicitly "meant" for them, the act of taking them on can feel purposeful.

David Bowie's song Heroes came to my mind. Could there be a connection within this topic?

Yes, David Bowie's "Heroes" can be interpreted as connected to the topic, especially if we consider the song's deeper themes of human resilience, self-imposed roles, and the choice to rise above limitations or circumstances. Here's how it might relate:

1. Choosing Heroism

In "Heroes", the protagonists decide to act as "heroes," even if only for a fleeting moment. This mirrors the idea of people taking on roles or responsibilities not explicitly meant for them, driven by a desire to transcend their reality or make a meaningful impact.

2. Empathy and Sacrifice

The characters in the song express a willingness to stand in defiance of their struggles (e.g., lovers by the Berlin Wall). This can be seen as an act of self-imposed heroism, where they carry burdens or make sacrifices that may not be "required" but feel necessary to them.

3. Aspirational Identity

The declaration "We can be heroes" speaks to the universal desire to matter, to rise above one's station, or to create meaning. This aspirational quality might explain why people take on things beyond their designated role—it's a way of embodying something greater.

4. Temporal Nature

The song emphasizes the impermanence of this heroism: "just for one day." This suggests that stepping into a role or burden may be a conscious choice rather than an identity, much like how people sometimes impose responsibilities on themselves for specific moments or situations.

Artistic Resonance

Bowie's exploration of identity and transformation often aligns with themes of self-imposed roles. "Heroes" doesn't directly explain why people take on unintended burdens, but it captures the emotional essence of striving, stepping up, and finding purpose, even in acts that might not strictly "belong" to us.

Would you like to explore this connection further, perhaps through a philosophical or artistic lens?

Yes

Exploring "Heroes" through a philosophical and artistic lens in connection to self-imposed roles and burdens reveals deep insights into human nature and our desire for meaning:

1. Philosophical Lens: Existentialism

Existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre argue that we create our essence through actions, even if those actions aren't predefined by societal roles. In "Heroes", the protagonists choose to be heroes, defying constraints like the Berlin Wall or external circumstances. This echoes the existential idea that individuals impose roles upon themselves to assert freedom and define their existence.

Why people take on unintended burdens:

Sometimes it stems from a sense of agency: "If no one else will, I will."

The act of stepping into a role—whether as a helper, problem-solver, or "hero"—can feel like an affirmation of personal meaning in an otherwise indifferent world.

2. Artistic Lens: Transformation and Performance

Bowie himself was a master of self-imposed roles, using personas like Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke to explore identity. "Heroes" reflects this artistic impulse to transcend limitations, suggesting that taking on roles (even unintended ones) is an act of creative transformation.

In art and life:

People often adopt roles not because they are "meant" to, but because doing so allows them to explore facets of themselves or their potential. This can be seen as a kind of performance—one that provides emotional or social rewards, even at personal cost.

3. Societal Context: The Weight of Collective Roles

In the context of the Berlin Wall, "Heroes" suggests that heroism often emerges in oppressive or restrictive environments. Similarly, people might take on unintended responsibilities when they feel society is failing to address something. The act of self-imposing roles becomes a response to external forces—whether out of hope, defiance, or necessity.

Heroism in the everyday:

Many everyday "heroes" are those who take on roles or burdens that society might not assign them but which they feel compelled to shoulder—parents, activists, caregivers, or even artists striving to make meaning.

4. Psychological Lens:

The Archetype of the Hero

Carl Jung's hero archetype resonates strongly here. Jung proposed that the hero is an inner figure representing the human journey of struggle, transformation, and triumph. When people take on unintended roles, they may be unconsciously aligning themselves with this archetype—striving for growth or an ideal.

In "Heroes", Bowie's protagonists aren't literal heroes in the traditional sense; they embody the archetype through their defiance and love. Similarly, individuals often adopt burdens as a way to enact their own inner heroic narrative.

Key Takeaways

Taking on unintended burdens can be seen as an existential choice, an act of artistic expression, or a reflection of societal needs.

Like the characters in "Heroes", we sometimes impose roles upon ourselves as a way to find purpose, assert freedom, or connect with something greater than ourselves.

Bowie's "Heroes" ultimately celebrates the human capacity for courage and transformation, even in small or fleeting acts, reminding us that self-imposed roles, while challenging, are often profound acts of meaning-making.

Would you like to delve deeper into any of these ideas—perhaps into the archetypal hero, Bowie's artistic philosophy, or existentialist thought?

yes, the existentialist thought

Exploring existentialist thought in relation to "Heroes" and the phenomenon of taking on unintended burdens offers rich insights into human behavior and meaning-making. Existentialism, rooted in the works of philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus, emphasizes personal responsibility, freedom, and the construction of meaning in an otherwise absurd or indifferent world.

Key Existentialist Concepts Related to Self-Imposed Roles

1. Radical Freedom and Responsibility

Sartre's famous dictum, "Man is condemned to be free," suggests that humans have no predefined essence or purpose—they must create their own meaning through choices.

In this light, taking on unintended burdens or roles is an act of radical freedom. Even if a role isn't "meant" for you, choosing to shoulder it becomes an assertion of your agency and responsibility.

For example, in "Heroes", the protagonists freely decide to act heroically, not because they are destined to, but because they choose to in defiance of their circumstances. This mirrors how individuals take on burdens as a way of exercising their freedom to shape their lives.

2. Bad Faith vs. Authenticity

Sartre contrasts bad faith (denying freedom and living passively within societal roles) with authenticity (embracing freedom and acting in alignment with one's chosen values).

When people take on unintended burdens authentically, they might be fulfilling a deep personal value, such as love, justice, or creativity. However, if they do so out of societal pressure or self-deception (e.g., to conform or avoid conflict), they may fall into bad faith. "Heroes" captures the authentic side of this phenomenon: the protagonists consciously take on the role of heroes, not because it's expected of them but because they choose to give their actions meaning.

3. The Absurd and Rebellion

Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, describes the human condition as absurd—a constant search for meaning in a meaningless universe. Rebellion against this absurdity is a way of asserting one's humanity.

Taking on burdens that aren't "meant" for you can be seen as an act of rebellion against the chaos or indifference of life. It's a way of saying, "This matters because I say it does."

Similarly, "Heroes" speaks to this rebellion: choosing to be heroic, even for "just one day," is a defiant affirmation of meaning in the face of impermanence and adversity.

4. Transcendence and Projecting Beyond the Self

Existentialists argue that humans are not static beings; we are always in a state of becoming, projecting ourselves toward future possibilities. Taking on unintended burdens can be part of this process of transcendence—seeking to grow, contribute, or connect with something greater than oneself.

In "Heroes", the characters transcend their immediate limitations (e.g., the division represented by the Berlin Wall) by imagining and enacting a moment of heroism, no matter how temporary.

Connection to Self-Imposed Roles

Why people take on unintended burdens:

Existentialism frames this as a way of confronting and shaping existence. When no one else steps in, or when life feels chaotic, taking responsibility can feel like a meaningful act of creation.

However, existentialists also caution against losing oneself in roles that feel imposed by society or circumstance rather than freely chosen. The key is to act authentically, aligning with one's own values and purpose.

Existential Tension in "Heroes"

The line, "We can be heroes, just for one day," encapsulates existential tension:

On one hand, it acknowledges the fleeting, impermanent nature of life and heroism (the absurd).

On the other, it celebrates the power of choice and the ability to imbue even a brief moment with profound meaning (authenticity and rebellion).

Bowie's characters don't need to be "destined" heroes—they choose heroism, despite its impermanence, asserting their freedom and defiance against the constraints of their world.

Existential Questions to Reflect On

1. Are the roles and burdens you take on truly your choice, or are they shaped by external pressures?

2. How do you find meaning in acts that might seem temporary or insignificant on a larger scale?

3. Can embracing fleeting moments of "heroism" or responsibility add authenticity to your life, even if they aren't expected or "meant" for you?

Would you like to explore how these ideas apply to specific experiences in your life, or delve deeper into any particular existential thinker's perspective?

yes, both

Applying Existentialist Ideas to Personal Experiences

Reflecting on how existentialism relates to your life, let's consider how the act of taking on unintended burdens or roles may resonate with your experiences:

1. Personal Choice and Responsibility

Are there times when you've felt compelled to take on responsibilities or burdens that weren't directly yours? For example, in your artistic or community endeavors, like launching the House of Culture Tintinto, did you feel that the role of organizer or leader was something you freely chose, or did circumstances subtly "assign" it to you?

Sartre would suggest asking yourself: "Am I choosing this role authentically, or am I acting out of bad faith by assuming it's expected of me?"

Reflection:

Did taking on these roles provide a sense of purpose, even if they were challenging? Were there moments when you questioned whether you imposed these roles on yourself unnecessarily?

2. Rebellion Against the Absurd

Projects like building a pavilion or contributing to culture in the Gambia might feel like acts of rebellion against the chaos or indifference of the world. These efforts may not attract as much interest as you'd hoped, but from an existentialist lens, their meaning lies in your commitment to them, not in external validation.

Camus would ask: "How do you continue to find meaning in your work, even when the world doesn't seem to care?"

Reflection: How do you personally navigate moments of doubt or futility? Does your art, writing, or gardening feel like a form of rebellion that asserts your humanity?

3. Authenticity in Relationships

In your relationship, you've expressed feeling like you sometimes carry emotional burdens or responsibilities that your partner doesn't share equally. Existentialism might frame this as an opportunity to reflect on authenticity versus self-sacrifice:

Are you authentically choosing to support your partner, or do you sometimes feel trapped in expectations that aren't shared or acknowledged?

Reflection: Could there be ways to renegotiate these dynamics, asserting both your freedom and your partner's? For example, sharing your emotional needs openly might feel vulnerable but align with an authentic life.

4. Finding Heroic Moments

Bowie's "Heroes" reminds us that even small, fleeting acts of defiance—like moments of joy, creativity, or connection—can be meaningful. Are there specific instances where you've felt like a "hero," even if only for a moment? These could be times when you acted courageously, created beauty through your art, or supported someone in need.

Reflection: How might focusing on these small "heroic" acts, rather than long-term outcomes, help you sustain meaning in challenging times?

Deepening with Specific Existential Thinkers

Jean-Paul Sartre: Freedom and Responsibility

Sartre believed that freedom is both a blessing and a burden.

In your life, where do you feel the weight of this freedom most intensely?

For instance:

Taking creative risks as an artist.

Choosing to invest energy into cultural or social projects in the Gambia.

Sartre's solution:

Embrace your choices, but also recognize that every choice reflects your values. He'd challenge you to ask: "What does this action say about the person I want to be?"

Albert Camus: The Absurd and Rebellion

Camus argued that life has no inherent meaning, but humans can rebel against this absurdity by living fully and passionately. Building the pavilion, cultivating your garden, or pursuing your artistic vision might all be forms of rebellion—saying "Yes" to life even in the face of its indifference.

Camus would ask: "Can you find joy in the process itself, rather than the outcome?" Even if the House of Culture Tintinto hasn't attracted much interest yet, the act of creating it could be its own justification.

Simone de Beauvoir: Ambiguity and Connection

De Beauvoir highlighted the tension between individual freedom and relationships with others. You might resonate with her ideas about mutual recognition: balancing your desire for freedom with your partner's, or finding meaningful ways to connect with people in the countryside.

She might ask: "How can you nurture relationships without losing your own sense of freedom and authenticity?"

Practical Applications

1. Reassess Burdens:

When you feel like taking on a role or burden, pause and ask: "Am I choosing this authentically? Does it align with my values?" If not, consider letting it go.

2. Find Joy in the Process:

Like Camus' Sisyphus, focus on finding meaning in the act itself rather than its results. Whether it's art, gardening, or writing, embrace the beauty of doing.

3. Celebrate Small Heroic Acts:

Look for moments when you've made a difference, no matter how small. These are your personal "heroic" contributions to the world.

4. Renegotiate Relationships:

In your relationship, consider expressing your needs with honesty and curiosity, as De Beauvoir suggests. Ask your partner how you can both share roles and emotional responsibilities more equally.

Would you like help exploring any of these ideas further or applying them to a specific situation?

To answer your question concerning House of Culture Tintinto, it was a mix. I freely decided to do it, but I also felt I had to do something essential

This mix of freedom and necessity you describe aligns closely with existentialist thought. Let's unpack it a bit further:

Freely Deciding Yet Feeling Compelled

1. Authenticity in Your Decision

Your decision to establish the House of Culture Tintinto reflects your creative agency. Even though you felt a sense of obligation to "do something essential," the act of founding the space was a conscious expression of your values—likely connected to art, community, and meaningful contribution.

Sartre would say that by choosing this path, you defined yourself as someone who takes action to create meaning, even in a challenging environment. This act demonstrates authenticity when it aligns with your deeply held beliefs.

2. The Feeling of Obligation

The feeling of having to do something can stem from an existential tension. Living in the Gambia as a "stranger" (as you've expressed), you might feel a drive to prove your place in the community or leave a meaningful mark. This need for purpose can feel urgent, as if inaction would be a denial of your freedom.

Existentialists like Camus would remind us that this tension—between the desire to contribute and the limitations of our environment—is what makes our rebellion against the absurd so human.

Is It "Bad Faith"?

Sartre's concept of bad faith is about acting in ways that deny our freedom. However, your decision doesn't seem like bad faith because:

It was rooted in your personal vision for what culture and art can offer.

It wasn't purely about societal pressure but came from a genuine belief in the importance of doing something "essential."

That said, the feeling of "having to" can sometimes push us toward internal conflict, especially when external validation is missing. This could lead to questioning whether the effort was worth it—a moment of existential doubt.

Existential Freedom in the Mix

Camus might argue that the act of creating the House of Culture Tintinto itself holds meaning, regardless of the outcome. The project represents a rebellion against stagnation, loneliness, or invisibility in the community. Even if interest has been limited, your effort asserts: "I am here, and I am creating."

Reflection Questions for Moving Forward

1. Do you still feel the House of Culture Tintinto aligns with your authentic values?

If yes, how can you continue shaping it in a way that feels meaningful to you, regardless of the external response?

2. How do you define "essential"?

What does this word mean for you personally? Is it about impact, visibility, or simply the act of doing something significant in your life?

3. What moments in the process have felt most rewarding?

Reflecting on these moments can help rekindle your sense of purpose.

Would you like to explore practical ways to rekindle interest in the project or are you more interested in understanding the philosophical side of this mix and obligation?

Both is important for me that people get interested in the project as well as the philosophical side. I think the philosophical side should inspire people to take part somehow

Your approach—blending the philosophical depth of your vision with practical ways to engage others—is powerful. Let's explore both aspects in a way that highlights how they can inspire interest in the House of Culture Tintinto while staying true to your values.

Philosophical Side: Inspiring Participation

1. Framing the House as a Shared Act of Meaning-Making

Sartre's and Camus's ideas emphasize the freedom to create meaning in a seemingly indifferent world. You could frame the House of Culture Tintinto as a space where everyone can contribute to this shared rebellion against the ordinary.

Inspiration: Position the House as a platform for people to express their individuality, celebrate their freedom, and create something together that couldn't exist otherwise.

2. Themes of Community and Authenticity

Use philosophy to make the project relatable. For example, you could discuss how authentic relationships (De Beauvoir) or acts of rebellion through creativity (Camus) are not just intellectual concepts but lived experiences that can unfold within the House.

Practical idea: Organize events, like discussions or art workshops, that explicitly explore these themes in action. You could use questions like: What does it mean to create authentically? or How can art challenge the status quo?

3. Heroism in Small Acts

Inspired by Bowie's "Heroes," invite the community to see themselves as everyday heroes who can shape the space. Highlight how small contributions—a piece of art, a shared story, or an idea—can ripple outward and become part of something meaningful.

Philosophical pitch: Share how their involvement represents a step toward crafting a collective narrative of beauty and purpose, even in a place where resources may be scarce.

Practical Side: Building Interest

1. Engage Through Personal Stories

People connect deeply with stories. Share your own philosophical journey—why you started the House of Culture Tintinto, the mix of freedom and obligation, and what you hope to achieve.

Idea: Host a storytelling evening, where you and others share personal stories about why art, culture, or community matters to them.

2. Create Accessible Entry Points

Offer ways for people to engage with the House that feel manageable and rewarding:

Art-making sessions:

Open to beginners and pros alike, focused on themes of self-expression or rebellion.

Community projects: Collaborative installations or garden work that make the space come alive.

Local partnerships: Partner with schools, artists, or other groups to co-create events or exhibitions.

3. Leverage Visibility

Sometimes, projects gain traction when people feel a sense of movement or buzz:

Use social media or local networks to post regular updates, like photos of the space, events, or behind-the-scenes glimpses of your work.

Organize small, visually impactful events, like pop-up exhibits or performances, that draw attention and curiosity.

4. Invite Local Philosophical Discussions

Organize informal discussions or talks that make philosophical ideas accessible:

For example, you could host a series called "Art and the Absurd: Creating Meaning in Our Community."

Include space for audience participation to make it feel inclusive.

5. Celebrate Milestones and Contributions

Highlight even small achievements to show that the House of Culture Tintinto is thriving. For instance:

Create a board or online gallery to showcase community contributions.

Host a "Heroes' Night" to thank participants and celebrate their work.

Combining Both Sides

Here's how you can blend the philosophical and practical approaches:

Event Example:

"Everyday Heroes: A Night of Art and Meaning"

Start with a short talk inspired by Bowie's "Heroes" or Camus' concept of rebellion, connecting it to the idea of community and small acts of creation.

Follow with an art-making session or performance where participants contribute their own interpretations of heroism.

End with a collective exhibit or discussion reflecting on the evening's creations.

Longer-Term Approach:

Build a narrative for the House of Culture Tintinto that emphasizes why it exists:

A space for individuals to embrace their freedom, collaborate, and find meaning together. Let this philosophy infuse everything you do, from events to daily operations.

Would you like to brainstorm specific event ideas, or focus on crafting a compelling narrative to attract and inspire others?

Yes, but then I have to go and prepare lunch. Or let's say I want to prepare lunch

It sounds like you're balancing freedom and responsibility even in your daily actions—deciding to prepare lunch while also feeling the necessity of it! Let's continue when you're ready. Preparing lunch can also be a meaningful act, so enjoy the process, and we can pick up the brainstorming when you return!

Alright, that's fine. I'll come back. Thank you so far for the lot of ideas.

You're very welcome! Take your time, and I'm here whenever you're ready to dive back in. Enjoy preparing your lunch, and I look forward to continuing our discussion later!

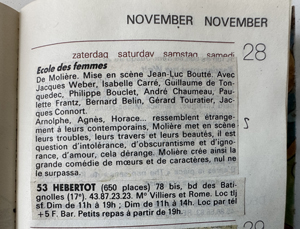

pasted into the 1992 agenda during the stay

at Cité Internationale des Arts Paris

The month is almost over. I feel restless. Maybe it's the wind that's making me anxious, or the feeling of not being needed. I don't know, I don't care, somehow, as I don't care about anything, the joy is missing.

Let's see what I've written on this day in past years. Maybe there will be repetitions.

In fact, in a total of 17 years, I've only found two entries for November 28th. It's not the date, but the sporadic way I write.

I'm aware of failure again, as so often. The feeling of not having lived up to the demands of a good artist prevails, or at least for the moment.

There are still a few old diaries and sketches that I haven't been able to get rid of yet. But even there I haven't found an entry that would be worth the space here. Some of the sketchbooks, four or five, are OK. I'll keep them. But the rest is garbage. Maybe, if I don't burn them, I'll make a self-portrait out of them someday.

2014

Friday, 28

you have made yourself wings, he said to me, i am still down on earth, so please leave me -

2013

Thursday, November 28

Reading books has changed since my cyberless childhood. That time when I had read a book - I always finished them and read one after the other - it was like I was embracing them, furnishing them proudly on my bookshelf; it was mine then. These days the meaning of books has become peripheral. There is lot of reading in internet and on electronic readers and the presence of a book is not that necessary. Of course, the content stays the same and you can fill your heart with it still, but for sure books lost their gravitas.

Saturday, 23

it's not the first time i've started like this. yes, my recurring question is whether writing helps. or should the therapeutic aspect be a driving force at all? no, it's not writing, it's the thinking, which comes before writing, that helps, its clearing up disorganized thoughts, when faced with a problem. and this time i don't mean the technical problems with the server, but questions of being. the older i get, the more i try to get everything under control, to be perfectly organized. i remember during young age, i took more risks. in fact, the fear of dying was less present. now that i'm old, i try everything to prevent it. focussed on living healthily i am supposed to live longer. no smoking, less alcohol, less saturated fats, no sugar etc. however, why can't i be as relaxed as i used to and instead getting more anxious? on the other hand, i live more consciously and my ability to control my life has improved. i know what i want and what i don't want.

I wrote this text at the end of last month and then decided to drop it. I had already addressed writing as such too often, was my verdict. Now it fell into my hands by chance - already deleted and found in the translation history. (there is a missing conclusion, not brought to the point, but i let it survive) A clue for today's entry - I had promised to write something. Actually about the German word exklusiv, which for me when I was young simply meant special or noble. It could even be ein exklusives Kleid (a plush dress), for example. The actual meaning of "exclusive" as opposed to "inclusive" only became clear now.

In Dakar, too, I thought about my age and that I don't have much time left. Today I saw the interview with Marina Abramović that she gave to SRF on the occasion of her exhibition in Zurich. An insightful conversation, a great woman. And then she said:

My real crisis I had when I got 70. When you are 70 that is such a big number. The main thing for me is how much time I have still to do what I have to do and that´s the only concern that I have. Because I have so much to do.

Marina Abramović and the Art of Overcoming

Saturday, 9

i see people with brochures in their hands - invitations, programs or signposts - walking through the multitude of exhibitions, but i don't see where or how to get the leaflets. so i walk through time, taking photos here and there. i don't bother to photograph the names anymore. i'm sure you can find them on search engines if you're interested in a work.

Thursday, 7

A few days ago we arrived in Dakar. Apart from the fact that Air Senegal delayed the flight twice, everything went well. Well, there were a few problems with the taxi driver, who didn't arrive at the airport on time (at 4 in the morning), which is understandable, but we had written to him beforehand and received no reply. So we took another one, which was of course annoying of him.

The room we rented is nice. Nothing to complain about, big bathroom, pleasant. We are right in the middle of the hustle and bustle of the many vendors. The street in front of our front door is always a bit wet, it seems that there is water damage that cannot be repaired.

This morning we were at the opening ceremony of the Biennale. Really nice, even if we (as always... or is it me to be always on the lose side) occupied the last seats up in the stalls. But great with wonderful music and dance performances.

Yesterday we picked up our batches. I had accredited us. But as it turned out, our batches weren't worth much. When we went to the vernissage of the exhibition at the Ancien Palais de la Justice this afternoon, we were turned away. We didn't have an invitation.

When we picked up the batches, I asked the man who handed them out to us what time the vernissage at the Ancien Palais de la Justice was. He answered somewhat grimly, 5 p.m. When I said goodbye to him and thanked him, he obviously looked past me. We were nobody. He didn't mention that we needed an invitation for the vernissage.

We then waited at the bus stop, I particularly disappointed. I asked a group, with The Wake cards in their hands that looked like invitations, if they had been there. A woman answered me, pointing to her invitation, that they were not of sufficient level to attend the vernissage. Aha, so we weren't the only ones who were turned away. Then a couple. I thought, they really look like they've already been through the whole thing. But no, them as well, directors of a cultural center in Togo, had to go home because they had no invitation.

Yes, what a pity Dakar, despite great ambitions, is unfortunately no different to Venice and the like.

Friday, 1

Art Space Work of the Month

Arthur Illies (1870-1952) - Jelängerjelieber (honeysuckle) colour etching, 1896

from the estate 1970, 33,5 x 50 cm